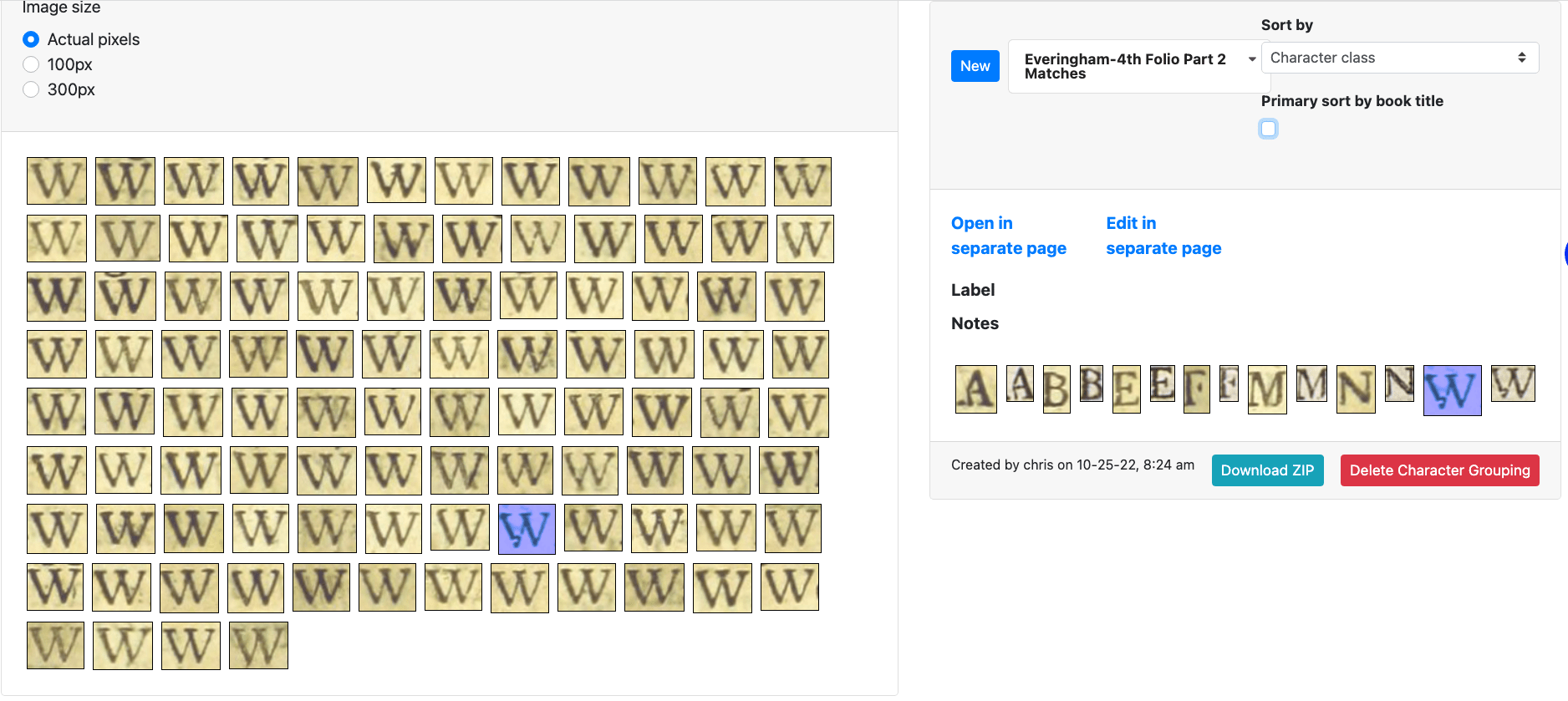

Screenshot showing how the virtual machine running on Bridges-2 displayed a correct match between a damaged capital W in Robert Everingham’s type collection (right, blue) and one from Shakespeare’s Fourth Folio (left, blue).

Infamous Typo in Shakespeare Folio Sheds Light on His Growing Status, Reduction in Status of Printing Profession in 17th-Century England

Shakespeare’s Fourth Folio contains a title-page typo, “RPINCE of DENMARK,” that has set historians chuckling — and wondering — for centuries. Who made that error? More importantly, what can the identity of the anonymous printer tell us about how the roles and status of Shakespeare, publishers, and printers were changing at the time? A Carnegie Mellon University team analyzed broken type in the Fourth Folio with an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm running on PSC’s Bridges-2 system to match the three parts of the book to three known English printers of the 17th Century.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

We can’t know what the 17th-Century printer who produced the part of Shakespeare’s Fourth Folio that contained most of the tragedies thought when he read “THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET RPINCE of DENMARK.” He probably winced.

Printing books at the time was incredibly tedious. First you fit lead-type slugs bearing backwards letters in line into a printing press. Then you smear it with a sticky ink, pressing the paper against the type to transfer the ink to the paper — which is why it was called a “press.” By the time anybody noticed the mistake, hundreds of copies may already have been printed. It might have been ruinously expensive to go back and fix it. Certainly, all the printed works of that time contain tons of typos. Just not as prominent.

Still, the printer knew he wasn’t going to put his name on the book. Maybe he was depending on some anonymity.

“There was this amazing challenge, a gauntlet thrown down by Fredson Bowers, who had studied this book … 50 years ago and said we would never know the printers of the Fourth Folio until we knew everything there is to know about seventeenth-century type … In effect, we said, ‘Fredson Bowers, hold our beer,’ because we felt like we had the tools.” — Christopher Warren, CMU

That anonymity contributed to one of the most enduring historical mysteries surrounding Shakespeare: Who did print the Fourth Folio? Why didn’t the printer(s) name themselves? What does it all say about Shakespeare’s status, as well as the changing relationships between writers, the publishers who paid for the books, and the printers who produced them?

CMU’s Christopher Warren, known for his group’s use of damaged type to identify printers of 17th-Century books and for telling us all who at the time was “six degrees from Sir Francis Bacon,” thought his National Endowment for the Humanities-funded team could solve that mystery. To do so, they turned to PSC’s NSF-funded, ACCESS-allocated Bridges-2 supercomputer.

HOW PSC HELPED

Warren’s team had adapted a technique recently reinvigorated by David Como of Stanford University. Como showed that the physical damage that soft lead type slugs inevitably suffered from being used could serve as a kind of fingerprint. He demonstrated, through painstaking work, that historians could match irregularities in individual letters to those in books whose printers were known.

Problem was, Como’s method was too painstaking. Expanding the work to larger books, and comparing them to dozens of printers’ known works, simply took too much expert time to be possible.

To solve this problem, Warren’s group turned to AI. An AI algorithm that trained on a dataset in which experts had labeled the “right” answers could, by random guessing over millions of tries, teach itself to match correctly. The researchers could then test the AI on data that hadn’t been labeled. Once the AI was accurate enough in testing, they could sic it on the vast data they’d need to analyze to get good results on a work as mammoth as the Fourth Folio.

Bridges-2 offered massive analytical ability through its number-crunching central processing units (CPUs), and seamless integration with its pattern-recognizing graphics processing units (GPUs). The system gave Warren’s group the power and flexibility to compare the Folio with a huge database of hundreds of known-printer works they and Samuel Lemley of the CMU Libraries had assembled.

“Early on, we requested … a virtual machine to host our database, which is where we’re writing all of the results from our image detection pipeline on the one hand, and then we built a Web application to pull on that database to display images and group images … A really great benefit for us is that it allows the … less technical members of our team, PhD students in English, for example, PhD students in history, to dive into the results of a lot of the technical work and do some classic, humanistically informed visual analysis.” — Christopher Warren, CMU

Another benefit was that PSC staff had designed Bridges-2 to simplify the construction of virtual machines (VMs). These are software-only computers within the computer, which can be set up to customize their workings to suit the needs of the user. In Warren’s case, it meant creating a VM that didn’t require students using the system to learn supercomputer programming.

As historians had expected, the CMU team found that three printers had produced different parts of the book. Robert Roberts, already suspected of printing the first part, did indeed produce it. London printer Robert Everingham printed the second. The third part, containing mostly tragedies as well as the tragic typo? John Macock, who once worked for Everingham. The team published their results in the journal Shakespeare Quarterly in June 2023 and have a more extensive discussion coming out soon in a book Lemley is currently editing.

It’s about more than outing poor Macock. Previous work by the CMU team identified the printers of works on individual liberty from a period when doing so could get you executed. Though anonymous, that work was an act of bravery that helped establish modern thought on human rights.

In the case of the Fourth Folio, the stakes weren’t as high. But the fact that Shakespeare was printed in folio format — the largest type of book at the time, which was also the most expensive and the most durable — reflected his growing status as an artist and a founder of modern English. Also, the CMU team’s results suggest that, increasingly, publishers’ names were printed in books but not printers’ names as part of a transition in which printers — lower-class workers than the big shots who bankrolled books — were losing status to publishers. Just as Shakespeare helped create modern English and English literature, this period helped give birth to today’s printing industry — or at least, as it existed before the Internet. But that’s another story.